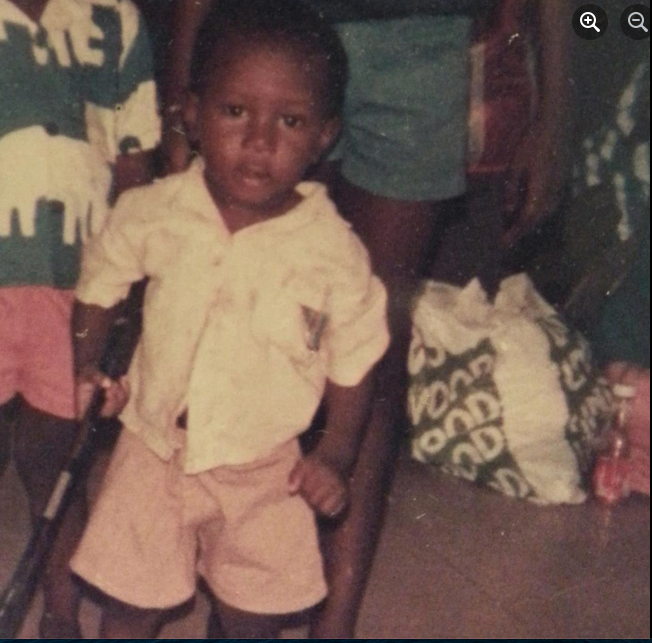

Public Health Stories: Cyril D. Loum

Cyril D. Loum serves as the Executive Director of Caring Ministries, Inc., which serves low-income families, immigrants, and refugees in becoming self-sufficient and finding sustainable housing in St. Louis.

The following profile is a portion of a collaboration storytelling effort between the City of St. Louis Department of Health, its Joint Board of Health and Hospitals, and Humans of St. Louis to examine public health in the St. Louis community.

““They’re not informed about racial injustice. They experience it, but they don’t know what it’s called.”

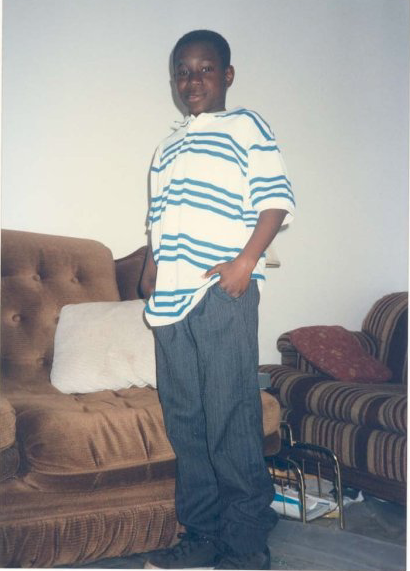

Loum: I’m an immigrant. I grew up dirt poor. I migrated to Ft. Wayne, Indiana with my family when I was seven. And we knew nothing about community. Bringing that forward to now, I came to St. Louis, went to UMSL and my passion became how to help immigrants in St. Louis. I’m the Executive Director of Caring Ministries, which helps immigrants and low-income families find affordable housing. And I’ve come to learn that there are a lot of things related to housing that immigrant communities aren’t aware of because of codes, because they aren’t accustomed to the system here, and because they can be taken advantage of. Health issues would rise up and they wouldn’t know what was going on. So I wanted to educate people in this community and in marginalized populations here because that was me. I was the kid from the family who didn’t know where to go or what to do when we arrived. We had no idea what was going on in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, then. Now there are way more immigrants and way more resources and providers, and the same thing happens to immigrants today. So I got involved in community building and as an entrepreneur in housing and urban development. And that’s what drove me to know there needs to be something done.

There’s a community called Hodiamont right by WashU, north of Delmar and not too far from The Loop. And I wasn’t even aware of the living conditions there because I just wasn’t engaged enough. I was in college, hanging out with my neighbors and friends, but did I sense any health issues in that area? Not at all. I call those who live there The Forgotten People. The Africans are from Congo, Somalia, Kenya, Sudan, and Burundi. The Latinos there mostly come from Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. Nobody really reaches out to them. Not enough people really know they exist in their little 181-apartment complex. My organization is mainly the only one that goes there to do outreach and educate families on how to become sustainable in St. Louis, about the opportunities available for them to grow holistically as individuals, and how to maintain good health.

The people who live in Hodiamont are in a new country, they’re surrounded by violence, they don’t know anybody. Refugees are dropped off there, they have to figure out a ton of things on their own, and I know it’s not easy. So if you don’t walk alongside them and educate them, they’re lost. They need to be aware of what’s happening with respect to health in the community to look after their own health. They need to know the disparities that exist here because they’re definitely not being informed about things like asbestos, lead poisoning, mold, mites, and poor ventilation. They’re not informed about racial injustice. They experience it, but they don’t know what it’s called.

One day I was walking with a kid around Hodiamont not far from his home and he was being bombarded with a bunch of name-calling. I said,"What’s wrong? Let’s keep walking." He said, "No, sir. Let’s turn around." For the first time, it hit me that I may not be seeing things like the people who live there. My skin color is the exact same, but I’m educated, I have a decent job, I’m not in that universe. I’m also a people person, so it was sad for me to see the racial injustice that kid faced. I might be naive to say this, but I never saw someone being called names so blatantly like that and from a person the same skin color as him. I was in a very awkward spot. As we walked back to his house, I told him, "Let’s walk through the neighborhood." I could see he was scared. I saw his fear and his fear was tense. At that point, my instinct was, "Let’s just go." We didn’t talk and we took another route to get back to his house.

When we got to his home, I chatted with him about life. Even though I’d never seen something like that before, it had happened to my fiancé. And since then, it happened to me. Anyway, I sat with him and shared, "Sadly, this is life. You’re judged by the color of your skin. And I know that is horrible. It should never ever happen. You’re gonna be made fun of. And you’re gonna be called more names than the names you were just called. But you’ve got to know that you’re stronger. You’re gonna go through it. But know that there’s a larger community that’s going to support you, walk along with you, and love you no matter what." He’s a great young man. Graduated from Roosevelt High School and is looking to go to community college. I’m super excited for him. And my heart goes out to individuals as such because they’re easily missed. Why? Because we think they’re not bringing assets to our communities. And they actually bring a wealth of knowledge.

If you go to the Hodiamont community, there’s a garden growing there. The food eaten from those crops is healthy. The people walk everywhere. And here I am, so lazy, trying to drive to a grocery store less than a mile from my house. People from Hodiamont are walking all the way to Grand from The Loop to get food too. Some of them don’t know the bus routes and have never used local transport. Still, they’re fighting to get all the way there across town. Not just that, but the people tell me they love walking. So they’re growing their own produce, have healthy eating habits, are walking around being active, and supporting each other in community — which we sometimes forget is a missing component of good health, because if you’re not in community, there could be mental health factors affecting you. I look at these things and realize these are assets. The way I see it, there’s no better or bigger person. We all have our gifts in certain areas. If we’re all able to connect in some way, we’ll make something great happen.

I’m hoping more people get involved in knowing communities like this. I want to be part of a community like that. I want to nurture a community like that. But, can you imagine someone from this population being informed about the health system? Public health’s job is to take care of the well-being of individuals in the community. It’s making them aware of the issues pertaining to their health. If you’re an immigrant or refugee and not well educated, it’s probably not part of your lifestyle to be engaged with your alderperson or the department of health. You might not know who is making the laws protecting your health. Your lifestyle is just working and doing things to go about life. So I’m happy with the department of health’s board and with Dr. Echols’s leadership, especially because they’re making it an issue to reach out to vulnerable populations.

The 181 apartments at Hodiamont are all occupied by immigrants and refugees. Refugees come through the International Institute, which has several entities they work with to place the families in homes. This particular complex has a budget fit for a number and size of families. And the families are mostly from East Africa and Latin America. Some have eight or more kids. And when you have a certain amount of money and you can only pay $550 for rent, finding a large enough space for that many people with that budget in South City is pretty hard. So Hodiamont is where many of them go through. From the media, we’ve known the health conditions of that housing complex are not great. But people are placed there, dropped off, and they figure it out themselves. They get connected with each other. Then when I visit, they’re complaining to me daily about the health conditions in their homes and there’s not much I can do apart from educating and connecting them with more resources. They may be used to coming from a place where they’re supposed to keep mum, so I tell them about tenants’ rights and how that’s what they have to let them know they have a voice. Here in America, here in St. Louis, they are permanent residents moving towards citizenship with documents, but it’s tough to see the situation because I feel like nobody helps them, nobody sees them.

During COVID, the City of St. Louis Department of Health board members got together and I shared organizations with them that are serving various ethnic groups from all over the world so we can connect with them and their leaders. I was able to send connections to our communication coordinator and now they have all this information about groups who can educate immigrant and refugee populations here about health and the vaccine and connect and partner with them. Being on the board, these are things that please me. Because when I was that young immigrant who first got to the U.S., there was no one trying to reach out to me or make me fully aware of important things like that here. I’d find out because of my friends I went to school with. And I didn’t know how reputable those things were when I ran home to tell my mom I heard something I thought she should know. She might or might not have believed them. So I’m excited that the job of the health department’s board is to take care of the wellbeing of this population in our community. We’ve now made it our intent to provide outreach to The Forgotten People. And that’s great because that’s how we’re going to give immigrants, refugees, and low-income people a voice. That’s how we’re showing we care for them. And, honestly, in the end, our titles don’t matter. The people I’m advocating for just know, "This is Cyril. He knows us. And he comes to us." I usually dress in shorts and a t-shirt, just living life. And that’s the way it should be because I need to relate to them.

Being from The Gambia, in West Africa, I experienced how much the country doesn’t invest in health. On the medical side, there was only one partially working X-ray machine for the entire country as recently as 2018. Maybe the country spends $5,000 a year from their GDP on health, and that includes the person’s salary. When I was growing up there, The Gambia was not a place where people saw health as an issue. You went about living life and things just happened. When my grandpa passed away, he was in his late 60s. He had a stroke and they told him to go home after he sought treatment. So he went home. Strong guy. And he died. But if my grandpa was in America, he wouldn’t have ended up in that situation to have passed away at such a young age. This continuously happens in my country because people think, "Everything’s okay. Just go about your life. And life ends when it ends." The government of Gambia doesn’t see itself as the entity responsible for the health of all its citizens, especially the disadvantaged. So health isn’t a conversation. When I Google "The Gambia," I see pictures of hospital beds that make me so sad. My oldest brother wanted to be a doctor and he pursued that career there. He’s sent me pictures of patients sitting on the floor and told me about how there’s such a high rate of death for women who are pregnant. My family wasn’t a poor family in The Gambia. We’re on the lower end of the rich people, and we weren’t super-rich. But the majority of immigrants and refugees in St. Louis grew up in worse conditions. And for refugees, I’d say much worse.

My fiancé came here from Cote d’Ivoire when she was 13 because of the war in Liberia, and she witnessed people in camps sleeping with four families in an 800 square foot space. Just horrible conditions and that’s what they’ve known for a while. Then, they come to America, transition to St. Louis, and anything is great compared to where they’ve come from. In the United States, we’re aware of what living standards are like and what it means to live in a great condition. So we have to educate new arrivals because, in their African context, their previous living conditions may have been great. But in St. Louis, it’s not great. You shouldn’t sleep on the floor with bed bugs on your mattress, rats running around your house, and asbestos in your walls. You shouldn’t have a ridiculous fever sitting at home when you should be at a hospital. Getting regular check-ups is something for the rich where they come from, so it’s not normal to them. They never had that. Then they arrive in this country and, I was going to say, we give them the bare minimum. But maybe we actually haven’t given them anything. Maybe we’ve just let them into the doors of our country and it appears that they’re happy when in fact we’ve failed in educating them. Organizations have had a great start, but we still have a long way to go.

When I was studying political science and legal studies, my aspiration was to run for office. And if you don’t care about the everyday person, you can run from all the way up there, but you don’t know how others are living day in and out. My goal was to make decisions that impact people because I saw that decisions that are made for us aren’t always for good. I saw how decisions in St. Louis that were made for us a long time ago impacted us in a bad way. Real estate, housing, redlining — all of that created stuff that hurt the community. So how do we have laws in place to make things fair? Injustice has been going on too long. There is more racial tension now than ever. Why? Because we still haven’t stepped up to make laws that say, "Enough." Growing up, I told myself, "Everything I see that’s wrong, I’m going to try to make right." And to do that, I have to understand what people are going through on a basic level. But I can’t just talk the talk. I have to live with them. Otherwise, there will be a disconnect. I’ll think that I’m hearing and seeing, but then realize I have to go to the root of something to identify with people even more.

I’m a passionate individual who wants to see the community better and stronger with everyone having an opportunity to be successful and with access to what they need. That’s the mindset I was brought up with by my mom and dad. And I hope we can see how laws are enacted and put into effect especially with housing. There shouldn’t be horrible living conditions for people. Contracts shouldn’t be signed to make renters feel like they can’t speak to their landlord about issues. There shouldn’t be racial injustice. We need to hold people accountable. If we don’t, it’s gonna keep going and going. A friend of mine from Morroco who looks Muslim got tired from being bombarded at his job. One day, he spoke up and told them to stop. You know who got fired? My friend, not the three adult men in their 50s. They didn’t get disciplined. But my friend, who’s helping his wife and raising their daughter — he got fired. Is that fair? Because that’s happening. That’s why it’s very important for us to look at our laws and how it affects everyone, not just from a big view and how it affects individuals who are comfortable. But how can we make sure minorities are not forgotten? How can we also educate them about laws that are in place and also their rights so they’re informed?

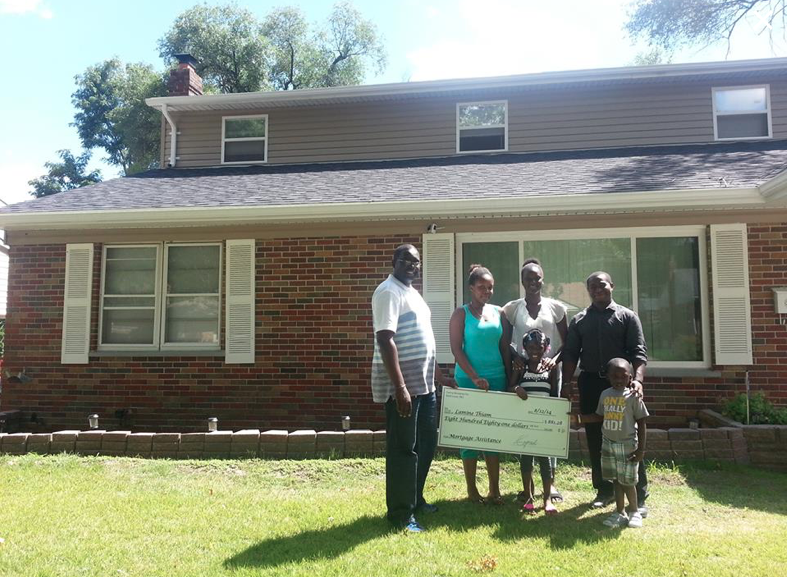

I’ve flipped about 90 homes for immigrants and refugees since 2011. This is a population that is struggling. They’re working in hospitals or hotels as cleaners and working their butts off. They come to me with a horrible credit score but hope for achieving the American Dream. They tell me their story and what they were going through back in their countries and just listening, I’m like, "How can I help them?" That’s why a lot of times through Caring Ministries, Inc. we work with banks like Justine Petersen and Prosperity Connection that can get them loans with $1,000 down or sometimes for free. And every step of the way, I am with them. It’s easier to just send somebody somewhere and tell them to go get something done. It’s different when there’s a familiar face with them holding their hand. Knowing these individuals can be taken advantage of easily, I’m right there with them educating them to say, "This is what’s going on."

Now, compared to the picture they have in their minds, the homes we’re seeing are horrible. Even though the bones are good, the places are messed up inside or might need a new roof. So we make sure everything gets fixed together. What’s good about this is that the family gets to walk with us, choose what’s going into their home, and see from the start, like, "Plumbing is really important, so let’s get that fixed. It looks like you may need a new roof in the next three to five years, so let’s put that in now. This is what the house is eventually going to look like, this is the cost, and this is what we’re going to do for you and with you." So we take broken homes that we call trash, that cause crime and all these other things in our city, and when these people come to me saying, "Cyril, we want that American Dream," I say, "It’s possible." In school, I wrote a poli-sci paper about how immigrants can revive the City of St. Louis. In placing families into those blighted homes, they can now revitalize them with their understanding of what it takes to build a home in a way that’s best for them.

Being a part of every step and how every dime was spent, once the families are in their homes, the place is done and it looks great. But it doesn’t stop there. We pay their closing costs. We also say, "Guess what? Things happen in life." Like my friend who lost his job, that could have happened to one of my clients. So we give them one to three months of mortgage assistance based on their income. It’s not so they go out and spend it. It’s for a rainy day, to teach them that education piece. So put that money into savings because things will come up. So many people have left the City of St. Louis. And to bring people back, we started looking at where there are stable communities with one or two homes available that we could revive. In doing that, we’re also helping to place people in a community. The families choose where. They walk around the neighborhoods, they get a feel for where they’d be comfortable, and then they pick where they want to go. Then families are now in a community that’s more vibrant and sustainable, even with respect to their health. Their neighborhood association might drop info on a flier at their door. Their neighbor might invite them to get vaccinated together. Now the people surrounding you love you because they’ve been seeing you for over 60 days around the house and they want to get to know who moved into the neighborhood. This way, we’re not just leaving them on their own. We’ve helped cultivate ways to give them a piece of that American Dream through education and community and it’s all connected.

To fix issues, it takes laws and the government coming together with companies and organizations to ask people, "What do you need?" and say, "We’re going to learn by you and bring that to you." It’s not about the glory of nonprofits and companies. It’s about the people we’re serving. Let them come first. So we need awareness for people to come together to help develop the community in a way that’s best for them. We’re going to have conversations with them and see what their assets are. We’re going to work towards their strengths. I used to sit on the board of the Immigrant Service Providers Network STL and there are immigrants who still don’t know what that is. So, first and foremost, we need to create more awareness. We need to be intentional about going door to door in a grassroots way, meeting people where they’re at, making them aware of what’s happening, and working with them to create solutions to make them stable on their own.

I literally get paid through Skandalaris Center, so why am I doing this for immigrants and refugees? Because they’re like me. I could have been that person. So let’s help anybody we see. Let’s walk with them and make it a better place for everyone. There are many immigrants like me and my family. And there is a church family who saw something in us, gave us an opportunity, plugged us into their community, and taught us things. Instead of bringing immigrants out of their community, go to them in your community. Be a friend. Reach out. Make sure that what you’re doing isn’t for your benefit, but to help other people. That’s how I see my job.

Immigrants bring so much to a community. When they know you and are connected to you, they will be obliged to you. They’re not going to go behind your back. They will go to the ends of the Earth for you. They are hard-working. They won’t cut corners. They’ll make sure they finish what needs to get done. They’re gonna give you their all — their work ethic, their passion, their honesty, determination, grit, and love for people. And as we know, they work the jobs that people don’t like to work. Let’s just say it. They will do whatever to provide for their family. They will build their community up. They will take care of the things that they have just as they take care of your family and help support other families in various ways. Immigrants bring a lot of things and they’re going to bring 100%.

If we don’t care about the public health of the immigrant community there will be situations like the one of the Somali man who died of COVID. He didn’t know where vaccines were being given and going to get vaccinated didn’t fit in his schedule. He was working a full-time job. On the weekend, he had to take care of his family of seven or more kids. His occupation wasn’t giving him permission to get the vaccines easily. Then there was communicating why it’s good to take the vaccine. There are many people frightened of it and what they hear is that white people are trying to hurt us. These are the reasons why that man died. You can’t blame someone for saying they want to take care of their family. But this is the kind of thing that can happen when we don’t reach out to educate and inform.

And we know the sad trickle-down effects if another person is lost. How can they go on living? Funerals cost money and where is the money coming from to cover them? Now, Mom has to take care of seven kids and the family’s fragmented. Maybe Mom’s forced to go out to make a living and if she’s not home, then the kids are at home taking care of each other. All of that can lead to poverty, health care not being taken care of, perhaps education being less of a priority. How can Mom fully nurture her kids? And, by the way, Mom doesn’t speak English at all. And as a single parent, she has to step up to play the role of both Mom and Dad in a country that’s new. What are we gonna do, put information online and hope this Mom sees it? C’mon, she’s not gonna go online. Let’s forget about that. Let’s talk about the relational piece. That’s why we need to be the ones to knock on her door to ask, "What do you need?" Hey, we’re all social workers. We just need to build relationships.

Help Us Improve This Page

Did you notice an error? Is there information that you expected to find on this page, but didn't? Let us know below, and we'll work on it.

Feedback is anonymous.